Decolonizing Reading Club: A Grandmother Begins the Story

In January 2021, LWF and the Lake Winnipeg Indigenous Collective (LWIC) collaboratively created a reading club to grow our teams’ understanding of Indigenous perspectives and experiences, truth and reconciliation, treaty obligations, and the history and legacy of colonization. Through group discussions on shared readings, this reading club genuinely created a brave space for personal and professional learning and reflection that hadn’t been possible in other workshops and trainings.

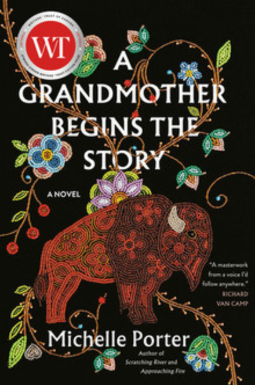

A Grandmother Begins the Story

by Michelle Porter

During our group discussion of A Grandmother Begins the Story, the 2023 debut novel from Métis writer and academic Michelle Porter, one of my colleagues shared the idea that “fiction teaches empathy.”

I had never conceptualized fiction in this way and the idea really resonated with me.

Porter’s book unfolds as a collection of short, loosely connected episodic chapters narrated by a constantly changing cast of characters including five generations of Métis women, several bison, two dogs, the prairie grassland and a car.

Taken as a whole, themes reveal themselves: the intergenerational effects of trauma experienced through residential schools; resistance, endurance and resilience (and how all three things are sometimes the same thing); and sacrifice.

Storytelling plays a multi-faceted role in this book, which I appreciated as a non-profit communications professional who spends a lot of time thinking about stories and how they can be used to inspire action and create change. Not only do the novel’s format and content reinforce the importance of storytelling within Métis culture, they also provoke questions worthy of reflection.

Who gets to tell their stories? Whose stories are valued and heard, and whose stories are mistrusted or ignored? Here, I think about the quote, “history is written by the victors,” and how repeated narratives within dominant cultures serve to reinforce systems of oppression and keep marginalized people marginalized.

Whose stories are exploited as a means to an end? Here, I think about the practice of using graphic imagery of people’s suffering as a tactic to solicit viewership (in the case of media) or donations (in the case of charitable organizations). This practice can provoke action, but is also reductive, voyeuristic, dehumanizing, disempowering and unethical.

Unlike some other fictional accounts of trauma, A Grandmother Begins the Story leaves much unsaid; the human characters we meet hold back when sharing their stories. To me, this felt like a statement on agency and consent: we are not owed all the gory, painful details – nor do we need them to get the point.

The book also explores how our biases shape the stories we tell ourselves. Presented with the same information, someone else might tell a completely different story. This idea plays out in a powerful scene between two sisters discussing their experiences with intimate partner violence. One frames her resistance as endurance through “pills and alcohol.” Her sister disagrees: “You resisted with ice and waiting and lasting longer than anybody else.”

My favourite stories were those told from the perspectives of the non-human characters. Within the worldview I was raised with, nature is a collection of resources to be appreciated, enjoyed and/or used. As I’ve learned more about Indigenous worldviews, I’ve been exposed to the idea that the land, water, animals and plants are relatives, no different than a human relative. This understanding is presented in a very literal way in Porter’s novel. We hear directly from bison as they grow up and fall in love and navigate changes beyond their control. We hear directly from the grassland about the connection between living creatures and the land, about renewal and growth and the interconnectedness of life.

Empathy is about understanding another person’s feelings, even if you don’t have personal experience with those feelings. Within A Grandmother Begins the Story is a lesson about the legacy of colonial violence and why it’s important to check one’s own privileges and prejudices before judging other people’s choices.

The book also serves as reminder that for many of us, our stories are not yet over. We have the ability to learn and change and own our stories – and in doing so, we can shape our future.

By: Marlo Campbell, LWF Senior Advisor, Communications

Want to read more?

Staff reflections on other readings can be found on our Decolonizing Reading Club web page.